Although IndyCar is currently nearly a single-make category, with just one chassis model and two engine options, in the past the category was marked by the creativity of its constructors, bringing to life a myriad of concepts, not always successfully.

1. Pat Clancy Special (1948): the bizarre six-wheeled single-seater that raced at Indianapolis

To understand the history of the Pat Clancy Special, we need to go back to the post-World War II period, when innovation in American motorsports was driven more by engineers’ intuition than by wind tunnel simulations. In 1948, in the midst of the era of front-engine roadsters, entrepreneur Pat Clancy decided to challenge the norm with a project that seemed more like something out of a science fiction movie than an Indianapolis pit: a car with six wheels, four of which were on the rear axle, all driven.

The idea, although unusual, was not without foundation. Clancy believed that by doubling the number of rear tires, the car could increase traction on the banked curves of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway — which would allow it to accelerate earlier out of corners and maintain higher speeds in a straight line. The concept was developed in partnership with Kurtis Kraft, a traditional builder of the time, which adapted a chassis specifically to house the mechanical assembly needed to drive the dual rear axle.

The engine was the ubiquitous Offenhauser 270-cubic-inch (about 4.4 liters) inline four-cylinder with dual overhead camshafts that had dominated open-wheel racing in the United States since the 1930s. The drivetrain, however, was specially modified to allow torque to be transmitted to two rear differentials, each driving a pair of wheels—an ingenious solution that, though rudimentary, worked.

The car was entered in the 1948 Indy 500 and driven by Billy DeVore, a veteran of American racing. Against the odds, the Pat Clancy Special qualified with the 20th fastest time and completed the 200 laps of the race, crossing the finish line in 12th place. For a first-generation experimental car, the performance was remarkable—even more so considering the technical challenges involved in aligning and balancing six wheels on a high-speed oval.

Despite its relative success, the concept was not pursued. The added weight, the complexity of the drivetrain, and the limited performance gains meant that the idea was soon abandoned. The car never raced again and remained a historical curiosity. Decades later, Formula 1 would test similar concepts, such as the six-wheeled Tyrrell P34 in the 1970s, but this too was never pursued in practice.

Today, the Pat Clancy Special is remembered as one of the most eccentric and ingenious projects in the history of the Indy 500. It represents a time when constructors’ creativity still had a place in major racing, and where the line between genius and madness was blurred—and often celebrated.

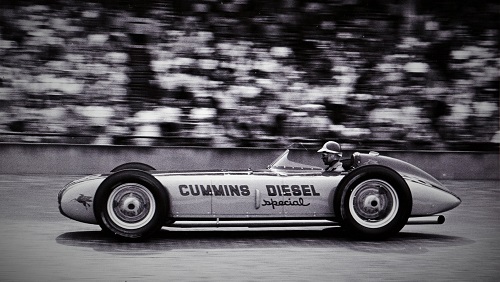

2. Cummins Diesel Special (1952): the only diesel car to take pole at Indianapolis

To understand the history of the Cummins Diesel Special, we need to go back to the 1930s, when the American company Cummins Engine Co., specialized in diesel engines, began using the Indy 500 as a proving ground and technological showcase. The idea was to show the public and the industry that diesel engines — until then associated with trucks and locomotives — could also be synonymous with innovation, performance and reliability.

The brand’s first participation was in 1931, with a diesel-powered car that completed the entire race without refueling, thanks to the engine’s low fuel consumption. Despite its modest performance, the feat attracted attention. Over the following decades, Cummins continued to invest in experimental projects, but it was in 1952 that its boldness reached its peak.

Based on a new USAC regulation that allowed larger diesel engines in exchange for a lower compression ratio and more limited revs, Cummins developed a six-cylinder in-line diesel engine with direct injection and turbocharging, something unprecedented in the history of the race. The engine was colossal: 6.6 liters, with around 400 horsepower, but its greatest asset was its resistance and abundant torque at low revs.

The car was developed with the help of Kurtis Kraft, and received a highly aerodynamic fairing for the standards of the time, with smooth side air intakes and a fully enveloping body. The set received the number #28, and was delivered to the experienced Fred Agabashian, a driver with consistent stints in Indy since the previous decade.

During training, the Cummins Diesel surprised everyone. The turbocharged power at higher altitudes helped the car post the fastest qualifying time, securing pole position for the 1952 Indy 500 — the first and only time a diesel-powered car topped the starting grid in the race.

In the race, however, the fairy tale was short-lived. The car started well, but faced overheating problems after 71 laps, retiring from the race. Even so, the impact of the performance was so significant that the organization decided to revise the technical regulations, imposing severe restrictions on diesel engines and forcing their disappearance from the grid in the following years.

The 1952 Cummins Diesel Special remains to this day as one of the greatest examples of successful innovation in the history of the Indy 500. Its legacy goes beyond the pole position: it demonstrated that diesel technology, when pushed to its limits, could compete with gasoline engines in one of the most demanding stages in world motorsports. Decades later, diesel engines would shine again at Le Mans, but never again at Indianapolis.

Today, the car is preserved at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, revered as an icon of alternative engineering and a symbol of an era when daring could mean leading the field — even if just for a day.

3. Kurtis Kraft Ferrari Roadster (1956): when Ferrari tried to tame Indianapolis the American way

To understand the curious Kurtis Kraft Ferrari Roadster, we need to look at the context of the 1950s, when Enzo Ferrari still dreamed of conquering America. Ferrari was already a dominant force in European racing, especially in Formula 1 and endurance racing, but Indianapolis was a world apart — a world dominated by robust American chassis and four-cylinder Offenhauser engines prepared to survive the 500 miles at constant speed.

The attempt to unite these two universes came from Luigi Chinetti, Ferrari’s representative in the United States and an enthusiastic promoter of the brand. Chinetti believed that Ferrari could also excel on the most famous oval in the world, and ordered an engine from Ferrari based on the 375 F1 model, a 4.5-liter V12 originally designed for European GPs but adapted to run at high speeds for long periods. The engine had about 380 HP and revved higher than the Offys, but its reliability was still a question mark.

To fit this Italian engine into a car with a real chance at Indianapolis, Chinetti hired none other than Frank Kurtis, the wizard of American roadsters. The body was hand-built by Kurtis Kraft from pressed aluminum, with typical Indy car lines: long, low and with the seat offset to the left, prioritizing stability on banked curves.

The result was the Kurtis Kraft-Ferrari Special, entered in the 1956 500 Miles with Bardahl sponsorship. The car attracted attention both for the sound of its V12 and for the Cavallino Rampante emblem printed on the American body. Bob Sweikert, winner of the Indy 500 the previous year, was chosen as the driver, which raised expectations even higher.

Unfortunately, the debut was disappointing. During practice, the car proved difficult to tune, with problems of overheating and poor weight distribution. The V12, designed for mixed circuits, suffered from the constant demand for high revs on the oval’s endless straights. To make matters worse, a problem with the fuel system prevented the car from even qualifying for the race.

The attempt to unite Ferrari and Indianapolis with this direct approach was never repeated. In the following years, Ferrari even considered its own projects for the Indy 500 — including the famous Type 637 chassis, which never raced — but the Kurtis Kraft-Ferrari Roadster remains the only real attempt to make a Ferrari engine roar at Indianapolis with a 100% American chassis.

Today, the car is restored and belongs to the Roarington collection, being one of the rarest and most eccentric machines in the history of Ferrari and American racing culture. It represents a time when technical exchange between continents was still experimental — and when the fusion of different philosophies, although romantic, did not always produce practical results.

4. Smokey Yunick’s Capsule Car (1964): The offset-engine roadster that went too far for Indy

To understand the history of the Capsule Car, we need to meet the man behind it: Henry “Smokey” Yunick, a self-taught engineer, former World War II bomber pilot, and perhaps the most creative and controversial tuner in the history of American motorsports. Owner of the legendary “Best Damn Garage in Town,” Smokey was known for his ingenious solutions that challenged (and sometimes circumvented) the technical regulations of NASCAR and USAC.

By the turn of the 1960s, the supremacy of front-engine roadsters at Indianapolis was beginning to be threatened by European rear-engine cars like the Lotus-Climax. Smokey, however, believed that roadsters still had potential—if they were radically rethought. That’s how his most extreme project was born: the Offset Roadster, nicknamed the “Capsule Car.”

The basic idea was to maximize lateral grip in IndyCar’s banked corners. To achieve this, Yunick repositioned the entire car—engine, chassis, wheels, and driver—to the left side, leaving the right side almost “empty.” This created an extremely asymmetrical weight distribution, with more weight on the inner (left) tires, allowing it to corner at higher speeds without compromising traction.

In addition to the extreme asymmetry, the car featured a completely enclosed and aerodynamic design, with the driver seated in a true metal “capsule” positioned close to the asphalt line, almost like a built-in sidecar. The engine was a turbocharged Offenhauser, also mounted in an offset position, with intake and exhaust pipes redesigned to compact the side profile of the car.

The car was entered for the 1964 Indianapolis 500, but obstacles soon arose. The USAC (United States Auto Club), concerned about the potential impact of the design on competitive balance and safety, demanded a series of changes to the car to allow it to participate. Smokey accepted some of the concepts, but refused to reconfigure essential elements of the concept. As a result, the car was not allowed to participate in the race, ending prematurely one of the most daring attempts to reinvent the American roadster.

Even without racing, the Capsule Car has remained etched in history as a symbol of innovation taken to the limit. Decades later, concepts of asymmetry and mass displacement would be successfully used in other categories, such as modern NASCAR, which uses deliberate offset in its oval chassis. Smokey was, as so often, ahead of his time — and outside the rules.

Today, replicas and remains of the Capsule Car can be seen in exhibitions and books about the history of IndyCar. It is remembered not only for its unusual appearance, but as an example of how, sometimes, radical innovation scares as much as it fascinates — and can be thwarted not by a lack of effectiveness, but by breaking too many paradigms, too quickly.

5. Stein-Huffaker’s Twin Porsche Special (1966): the twin-engine Porsche that challenged the Indy 500

In the 1960s, the competition at Indianapolis was fiercer than ever. The Indy 500 was undergoing a significant technical transition, with the traditional front-engine roadsters beginning to give way to new rear-engine cars inspired by Formula 1. It was in this context of change and innovation that, in 1966, the Stein-Huffaker Twin Porsche Special was born, a unique and bold project that stood out not only for its eccentric configuration, but also for its ambition to apply advanced European technology to the most famous oval in the world.

The project was conceived by Jack Huffaker, an experienced chassis engineer, and Bill Stein, owner of a single-seater racing team. They teamed up to create a car with a “twin-engine” engine configuration, something never before seen at Indianapolis. Instead of a single mid- or front-mounted engine, the Twin Porsche Special had two 2.0-liter Porsche engines, each powering one of the axles, resulting in an all-wheel drive car.

The choice of Porsche engines was clearly an attempt to introduce the refined engineering and performance of European units into the traditional American championship. Porsche, known for its high-revving and efficient engines, was an ambitious choice, but the design also had its limitations. The “twin-engine” configuration created a considerable technical challenge, requiring extremely complex drivetrains to integrate the two engines efficiently and in sync.

The car made its debut in the 1966 500 Miles, but, as expected, things did not go according to plan. During practice, synchronization problems between the engines arose, making the car extremely difficult to control. In addition, engine temperatures began to rise above expectations, causing mechanical failures and performance difficulties. The Twin Porsche Special failed to qualify for the race, being eliminated in the early stages.

Although the car never competed, the project attracted attention at the time for its boldness and for its attempt to incorporate advanced German technology into an event largely dominated by American manufacturers. The idea of two engines powering the car was a huge mechanical and logistical challenge, but it was also a reflection of the innovative and experimental mindset that dominated motorsport in the 1960s. The Twin Porsche Special has gone down in history as an example of how the spirit of innovation could be simultaneously visionary and impractical.

Decades later, the concept of multi-engine cars would continue to be an area of interest in a few projects, but none ever competed in any significant way in the Indianapolis 500. The legacy of the Twin Porsche Special is therefore that of a project that showed the lengths to which engineers were willing to go in an attempt to innovate — and how, sometimes, radical innovation can be more of a historical curiosity than a viable solution.

Today, the Stein-Huffaker Twin Porsche Special is remembered as one of the most audacious and technical experimental cars in IndyCar history, an example of how the desire to explore the limits of engineering can lead to truly original creations, even if they ultimately fail to achieve competitive success.

6. STP-Paxton Turbocar (1967): the turbine that almost won the Indy 500

In the 1960s, the quest for technological innovation in motorsports was reaching new heights, and the Indy 500 was the stage for some of the most daring ideas ever seen on the track. After the success of turbines in endurance and speed races, the application of gas turbine engines in racing cars seemed to be the next logical revolution. It was in this context that the STP-Paxton Turbocar was born, a project that promised to transform grassroots motorsports with its futuristic proposal.

The car was designed by Andy Granatelli, the charismatic executive of STP, in partnership with Paxton Products, a company specializing in superchargers. Granatelli believed that turbine engines, with their high power, low relative weight and continuous operation, were the future of racing. And, instead of adapting a turbine to a regular car, the project started from scratch, with the engine as the central element of the project.

The Turbocar was powered by an Allison J-34 gas turbine, originally developed for jet aircraft. This engine generated around 550 hp, with continuous power delivery and no need for a gearbox — a significant mechanical advantage, eliminating components subject to failure such as the clutch and gearbox. The chassis, developed by Ken Wallis, was built from aluminum and fiberglass, and had four-wheel drive to help tame the turbine’s power delivery.

With promising performance in testing, the Turbocar qualified on the second row of the grid, starting in second place among the 33 cars that made up the grid for the 1967 Indy 500. From the start of the race, driver Parnelli Jones, champion of the Indy 500 in 1963, showed the car’s potential: the Turbocar led 171 of the 200 laps, an almost absolute dominance of the race.

However, this technical superiority bothered the USAC (United States Auto Club), the organization that organized the race. To “equalize” the performance of turbines in relation to conventional engines, USAC imposed air intake restrictors, limiting the turbine’s power by forcing less fuel. Even with this limitation, the Turbocar still proved to be more efficient and competitive than its piston-powered rivals.

The dream, however, collapsed just a few kilometers from the end. With only 3 laps to go before the checkered flag, a small failure in a transmission bearing forced Parnelli Jones to abandon the race, leaving victory to A.J. Foyt, who was driving a traditional roadster powered by a V8 engine.

The failure was tragic, but the impact of the Turbocar was immense. Its performance provoked an immediate reaction from USAC, which imposed new and even more severe restrictions on gas turbine cars in the following editions, making them practically unviable competitively. Even so, the concept was revived the following year with the Lotus 56, another turbine car also sponsored by STP.

Although the Turbocar did not win, it went down in history as one of the most innovative and nearly victorious cars in Indy 500 history. Its legacy remains as a symbol of Andy Granatelli’s futuristic vision and the technical daring of an era when anything seemed possible.

7. Lear Vapordyne (1969): The bizarre steam car that tried to race at Indianapolis

To understand the creation of the Lear Vapordyne, we need to go back to the late 1960s, when eccentric businessman Bill Lear — best known for creating the Learjet executive jet — decided to invest in a concept as bold as it was unlikely: a steam-powered racing car. At a time when internal combustion engines dominated motorsports with increasingly refined technology, Lear wanted to prove that there was room for alternative, “cleaner” and quieter solutions.

The idea for the Vapordyne was born from a mix of ecological ambition and pure experimentalism. Bill Lear, a staunch advocate of sustainable technologies, believed that modern steam engines could compete in performance with those powered by gasoline. The basis of the project was a closed-cycle steam turbogenerator propulsion system, powered by a mixture of water and a special pressurized fluid. This system, although sophisticated in theory, was extremely complex in practice, and generated several challenges related to weight, heat dissipation and engine response time.

To bring his idea to life, Lear hired racing engineer Bob Gurr and formed a technical team dedicated to developing the car. The Vapordyne’s chassis was futuristic and aerodynamic for the time, with an aluminum frame and a pointed body. The goal was to enter it in the 1969 Indianapolis 500, one of the most prestigious stages in world motorsports. IndyCar was known for allowing (to a certain extent) experimental cars — which made the venture less absurd than it might seem.

However, preliminary tests soon showed that the steam engine was no match for the powerful V8s of the competition. The system took too long to reach the ideal operating pressure, in addition to making the car excessively heavy. The throttle response itself was slow, and the top speed was not exciting. Instead of a revolutionary innovation, the Vapordyne proved to be more of a conceptual project with chronic difficulties in competitiveness.

Despite this, the car was entered in the 1969 Indianapolis 500, but never made it to an official lap of the oval. Bill Lear abandoned the project shortly thereafter, focusing his attention on other inventions, such as developing navigation systems and more efficient airplanes.

The Vapordyne has become a curious footnote in IndyCar history, but it remains a symbol of an era when racing still allowed—and sometimes even encouraged—radical experimentation. Although the idea of steam-powered cars on the racetrack has never been taken seriously again, Lear’s project is a fascinating reminder of how fine the line between genius and madness can be in motorsports.

8. Jim Hurtubise’s Mallard-Offenhauser (1972): The last of the roadsters in a world of wing cars

To understand the creation of the Mallard, the legendary last Indy roadster, you need to know the person who designed it: Jim Hurtubise, one of the most charismatic, stubborn and beloved characters in the history of the Indianapolis 500. Hurtubise was a true defender of the “old guard” — at a time when American motorsports was undergoing a profound technical revolution.

During the 1960s, front-engine cars, known as roadsters, dominated the Indianapolis grid. Powerful, robust and traditional, they were driven by true speed cowboys. However, with the arrival of mid-engine cars and aerodynamic concepts inspired by Formula 1, the Indy scene began to change drastically. In 1965, Jim Clark won the race in a Lotus, marking the beginning of the era of rear-engine cars. From that moment on, roadsters became obsolete overnight.

But Hurtubise refused to accept this.

In 1968, he introduced the Mallard-Offenhauser project, an all-new front-engine roadster built from scratch when all other teams had already switched to rear-engined cars. Called the Mallard, the car was developed with the help of Quinn Epperly (designer of the famous Watson roadster) and featured a turbocharged Offenhauser engine. Hurtubise believed that with lightness, good handling and a strong engine, it was still possible to compete with the rear-engined cars — even if this belief was purely emotional.

During the early 1970s, the Mallard attempted to qualify for several Indy 500s. In 1972, the car underwent updates and appeared with a clean look and lightened structure. The qualifying attempt that year was epic: Hurtubise went through the inspection procedure, warmed up the car, and lined up for the qualifying lap—but when the crucial moment arrived, he parked the car, opened the hood, and revealed a keg of beer and a bunch of plastic cups, inviting the entire crew and the marshals to toast in the pit lane. A gesture that became legendary.

The episode sealed the Mallard’s status as a folkloric piece of the race’s history. Still, Hurtubise kept trying to enter it, even if only as a symbolic maneuver, until the end of the decade. Over time, the car ceased to be a competitive attempt and became a walking tribute to the spirit of IndyCar’s golden years.

The Mallard-Offy never officially raced at Indianapolis, but that didn’t stop it from earning its place as an icon of romantic resistance to technological evolution. Jim Hurtubise passed away in 1989, but his roadster remains on display in museums and vintage meets as a reminder that in Indianapolis, winning isn’t always what matters—sometimes defying the odds is a victory.

9. Eagle Aircraft Flyer Special (1982): An airplane disguised as a racing car

The story of the Eagle Aircraft Flyer Special begins with a bold premise: what if we applied the concepts of aeronautical design directly to an Indy 500 race car? That was the starting point for engineer Dean Wilson, a lightweight structure specialist from the aerospace industry, who in the 1980s decided to put his ideas to the test on the biggest stage in American motorsports.

Wilson was no stranger to the racing world — he had previously worked with Dan Gurney on the All American Racers — but his 1982 project took interdisciplinary thinking to another level. He founded Eagle Aircraft, a company specializing in small aircraft, and from there created the Flyer Special, a car completely outside the traditional Indy car mold.

The Eagle Flyer chassis was developed with extensive use of aircraft-grade aluminum and composite panels, which made it extremely light and rigid. The body was designed with a focus on high-efficiency aerodynamics, with flowing lines, a thin-section profile and air intakes inspired by the laminar flow of experimental aircraft. The suspension was innovative, with geometry optimized to maintain ideal contact with the asphalt in the high-speed curves of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

At the heart of the car was the Cosworth DFX engine, a 2.65-liter turbocharged V8, practically standard in the category at the time. The goal was not to reinvent the engine, but rather to maximize the potential of the ultra-light chassis and aerodynamic efficiency. With around 750 HP and a total weight below the grid average, the Flyer Special promised to be a surprise — at least on paper.

Unfortunately, the execution did not match the ambition. The car faced several technical problems during qualifying tests, including instability at high speed and difficulty in adjusting the suspension. The design, although advanced, was also extremely sensitive to variations in temperature and aerodynamic pressure, which complicated the life of the technical team. In practice, the Flyer was unpredictable and unreliable.

The car was entered for the 1982 Indianapolis 500 with driver Jerry Karl, but failed to record a time fast enough to make the grid. After failing to qualify, the project was quickly shelved. Wilson returned to his aeronautical career, and the Flyer Special became a forgotten rarity—one of the many bold experiments that the Indy 500 has inspired throughout its history.

Despite its failure on the track, the Eagle Flyer is remembered as one of the most technically interesting cars to ever attempt Indianapolis. A true bridge between two worlds: that of racing engineering and that of experimental light aviation.

10. Penske PC23 Mercedes 500I (1994): The car that exploited a loophole in the regulations and was banned after winning

To understand the history of the Penske PC23 Mercedes 500I, it is necessary to understand the technical and political context surrounding the Indy 500 in the early 1990s. In 1994, CART (Championship Auto Racing Teams) was still the main category for American single-seaters, and Indianapolis, under the management of USAC, allowed the entry of cars with different technical configurations — which created a hybrid regulation, full of exceptions and loopholes to be exploited.

It was in this scenario that the genius of Roger Penske, combined with the engineering of Ilmor and the talent of Mario Illien, found a flaw in the regulation. The loophole in question concerned pushrod engines, a type of simpler architecture, used in the early days of Indy, and which had been maintained in the regulation to encourage small teams with production-derived block engines. To “help” these teams, USAC allowed these engines to use more turbo pressure (55 inches of mercury, compared to 45 for conventional DOHC engines) and a larger displacement (3.43 L compared to 2.65 L for standard engines).

Penske saw this as a unique opportunity: what if we built a pushrod engine from scratch, with cutting-edge technology, just to take advantage of this performance advantage? That’s how the Mercedes-Benz 500I engine was born, developed in secret by Ilmor for over a year. Despite using pushrod architecture (camshaft in the block and pushrods to actuate the valves), it was a modern unit, made with the best materials available and capable of spinning at absurdly high revs for this type of engine.

The result was an engine with over 1,000 HP, a value about 200 HP above what the DOHC Cosworth and Honda engines could deliver at the time. The engine was installed in the exceptional Penske PC23 chassis, a car that was already dominant in the CART stages, with refined suspension, excellent weight distribution and refined aerodynamics.

The debut of this “combo” in Indianapolis was overwhelming. In May 1994, Al Unser Jr. won the race after leading 119 of the 200 laps. The performance of the Penske-Mercedes was so superior that its rivals were astonished. Paul Tracy, in the same car, also had the pace to win, but retired due to mechanical failure. It was a technical humiliation for the rest of the field.

Immediately after the race, USAC changed the regulations, drastically restricting pushrod engines and effectively banning any attempt to repeat the feat. The 500I was retired with 100% success: it competed in a single race, won, and was banned.

The case generated enormous debate in the paddock. Some saw it as a masterstroke by Roger Penske, who simply followed the rules to the letter. Others saw it as an unsportsmanlike distortion. Either way, the PC23 Mercedes 500I went down in history as one of the greatest examples of clever engineering — and how to win, because the creation of such a dominant car meant that the rules had to be rewritten.

Bonus: Quin Epperly “Fuel Injection Special” (1955): The streamliner that anticipated the future — and was cut short by tragedy

In the 1950s, the Indy 500 was dominated by conservatively designed roadsters with open bodies and rudimentary aerodynamics. However, engineer Quin Epperly, in collaboration with mechanics Jim Travers and Frank Coon—known as the “Indy Whiz Kids”—sought to shake up this tradition. Commissioned by Howard Keck for two-time champion Bill Vukovich, the Fuel Injection Special was conceived as the first American race car designed using a wind tunnel, with the goal of minimizing aerodynamic drag and maximizing straight-line speed.

The design featured a fully faired body with covered wheels and sleek lines reminiscent of the German Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz streamliners of the 1930s. A notable difference was the adjustable rear “lift”—a precursor to modern spoilers—that allowed the driver to alter the aerodynamic balance during the race. Additionally, the car had an asymmetrical layout, with the cockpit and engine offset to the right, optimizing weight distribution in the Indianapolis circuit’s predominantly left-hand corners.

The heart of the streamliner was a 270-cubic-inch Offenhauser engine with dual overhead camshafts and fuel injection, mounted in a lightweight, rigid chassis. The combination promised superior performance, but the car was not ready in time for the 1955 Indy 500. Vukovich instead opted to race a traditional Kurtis Kraft for Lindsey Hopkins’ team.

Tragically, during the race, Vukovich was fatally injured while leading, ending not only his career but also Keck’s involvement in motorsports. The unfinished streamliner was stored for decades until it was acquired by Jimmy Dobbs, who, with Epperly’s help, completed and restored the car to its original design. In 2019, the vehicle was auctioned for $385,000, and has been recognized as a landmark in American automotive engineering.

The Fuel Injection Special remains a symbol of interrupted innovation, representing a futuristic vision that, although it did not compete, influenced race car design for decades to come.

Sources:

Two Wheels Too Many: The Story of the Pat Clancy Special. Available at: https://www.macsmotorcitygarage.com/two-wheels-too-many-the-story-of-the-pat-clancy-special/.

No.28 CUMMINS DIESEL SPECIAL TO RUN WITH MOTORSPORTS GAME-CHANGERS AT GOODWOOD. Available at: https://www.cummins.com/news/releases/2017/06/23/no28-cummins-diesel-special-run-motorsports-game-changers-goodwood.

1956 Barahl Special. Available at: https://roarington.com/media-house/directories/cars/ferrarikurtis_kraft_barahl_special_1956.

Another Look at Smokey Yunick’s Capsule Car. Available at: https://www.macsmotorcitygarage.com/another-look-at-smokey-yunicks-capsule-car/.

Stein-Huffaker Twin Porsche Indy Car. Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/exoticcarspage/stein-huffaker-twin-porsche-indy-car.

STP-Paxton Turbocar, 1967. Available at: https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_882080.

Was Bill Lear’s steam-powered Vapordyne more than Indy-racer vaporware? Available at: https://www.hagerty.com/media/automotive-history/was-bill-lears-steam-powered-vapordyne-more-than-indy-racer-vaporware/.

Jim Hurtubise and the Mallard-Offy. Available at: https://www.macsmotorcitygarage.com/jim-hurtubise-and-the-mallard-offy/.

Eagle Aircraft Flyer: a bizarrice perigosa criada por um curioso na Indy. Available at: https://projetomotor.com.br/eagle-aircraft-flyer-special-indy-indianapolis/.

Como Penske e Ilmor construíram um monstro que dominou a Indy em 1994. Available at: https://projetomotor.com.br/penske-ilmor-mercedes-indy-indianapolis-1994/.

1955 Quin Epperly “Fuel Injection Special” Indy 500 Streamliner. Available at: https://www.sportscarmarket.com/profile/1955-quin-epperly-fuel-injection-special-indy-500-streamliner.

The 1955 Indy 500 Crash Killed a Legend, and the First-Ever Wind-Tunnel-Designed Race Car. Available at: https://www.autoevolution.com/news/the-1955-indy-500-crash-killed-a-legend-and-the-first-ever-wind-tunnel-designed-race-car-231763.html.