As motorsport fans will already know, next weekend will see the start of another edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the most traditional and important race in world motorsport. For those who are not familiar with it, this race was created in 1923, at a time when Grand Prix racing was the most popular form of motorsport in Europe. Instead of focusing on which company was able to make the fastest car, in the 24 Hours of Le Mans manufacturers should focus on having the most efficient cars, in order to achieve a balance between performance and reliability. Held on the La Sarthe circuit, a circuit that combines sections of a race track with roads that connect the cities of Le Mans, Mulsanne and Arnage, it is the greatest endurance race in motorsports, and is part of the Triple Crown of Motorsports, considered, along with the Indianapolis 500 and the Monaco Grand Prix, the pinnacle of a racing driver’s career. In the coming days, we will enter a countdown, presenting some interesting facts about the race and its participants.

And to start, nothing better than the most curious cars to have participated in the history of the race, as we can see in this top 10:

1. Cadillac Series 61 Coupe De Ville “Le Monstre” (1950)

When American Briggs Swift Cunninham decided to participate in the 1950 edition of Le Mans, he decided to use the powerful OHV V8 engines from Cadillac. His initial idea was to use these engines with Ford bodies, but as the organization considered the proposal inadequate for the spirit of Le Mans because they resembled too much a hot rod, Cunninham decided to buy two Cadillac Series 61 Coupe De Ville Series 61. The first kept the original body, but for the second Briggs sought the support of aerodynamic engineer Howard Weinman, who designed a new body, all in aluminum, much more aerodynamic and lower than that of the street car, but with an appearance of questionable taste, to say the least, which led the French press to nickname the model Le Monstre, or The Monster. Despite the nickname and the fact that the cars had not undergone any testing up until the time of the race, both finished the race, with Le Monstre taking the checkered flag in 11th place.

2. Nardi Bisiluro 750 LM (1955)

In 1955, Le Mans was dominated by powerful cars such as the Jaguar D-Type and Mercedes 300 SLR, but Italians Mario Damonte, Carlo Mollino and Enrico Nardi took a completely different path: instead of creating a heavy car with a large engine, they created a small model with a 734 cm³ four-cylinder engine. Its design, in the best catamaran style, had the driver and fuel tank on one side and the engine and transmission on the other. In addition, it had drum brakes on all four wheels and a central airbrake activated by a pedal. The Italians’ bet was that they could compete with the big brands using a light (only 450 kg) and simpler car, but the plan backfired when the small car was taken off the track during training by the displacement of air from a Jaguar that was overtaking it. Unfortunately, the car could not be rebuilt in time to participate in the race and today it is in the National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo Da Vinci, in Milan.

3. Rover-BRM (1963-1965)

In the early 1960s, the automotive industry was moving towards using turbines instead of internal combustion engines. In an attempt to follow the same path as the aeronautical industry, several projects emerged, such as the famous Chrysler Turbine. Another company working on this idea was the British Rover, which had presented the Jet1 turbine car prototype a few years earlier. The crucial point in making the model a reality was the participation of the BRM Formula 1 team, which provided Rover with the chassis of the car that Richie Ginther used to compete in the 1962 Monaco GP. The turbine and a single-speed transmission were mounted on this chassis, as well as a spyder-style body made of aluminum. The car then raced at Le Mans in 1963 in the experimental car category, finishing 8th in the final standings. For 1964, a new body, this time a closed coupe, was created and the engine received updates, but for reasons not disclosed, Rover withdrew from the competition. For 1965, the model was finally entered in the prototype class with engines up to 2 liters, with a pair of drivers that would be the envy of any team: Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart. Suffering from problems throughout the race due to damage to the turbine blades after a mistake by Hill, the team still managed to finish the race in tenth place overall, and eighth in the prototype category.

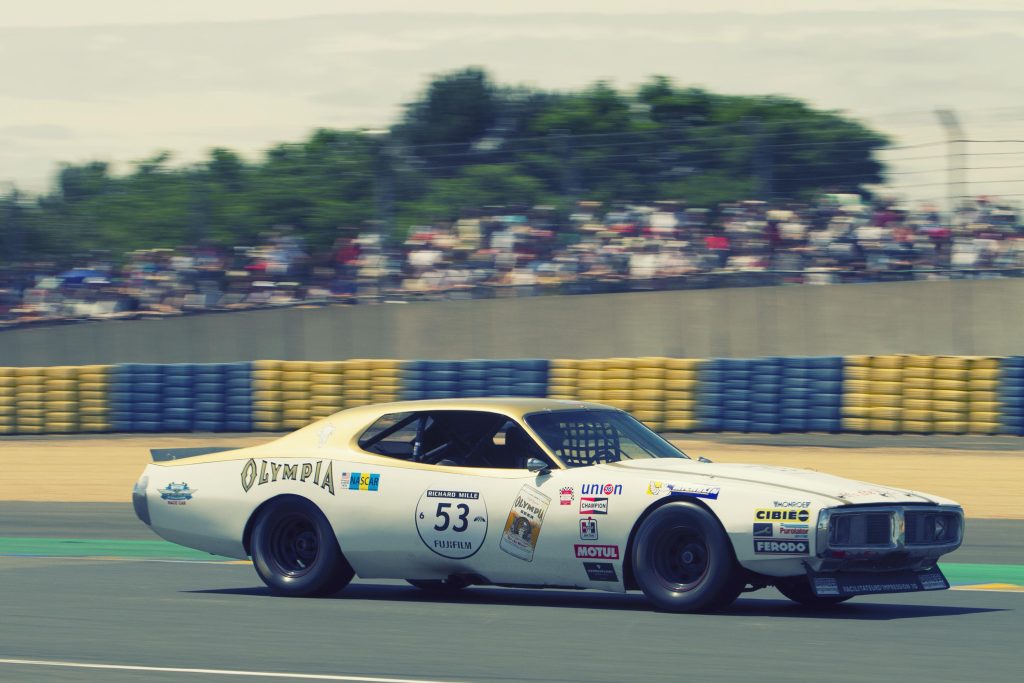

4. Dodge Charger NASCAR (1976)

After the boom in popularity experienced in the 1960s and early 1970s, largely due to the Ferrari-Ford and Ford-Porsche rivalries, the oil crisis came along and caused the 24 Hours of Le Mans to start losing some of its popularity. As a way of trying to combat this trend, the ACO began inviting prominent athletes from a variety of categories around the world to bring their cars to compete. This culminated in 1976 with the participation of Hershell McGriff and his son Doug McGriff in a Dodge Charger taken straight from NASCAR competitions. In addition to him, that same year a Ford Torino from the American category also competed, driven by Americans Richard Brooks and Dick Hutcherson and Frenchman Marcel Mignot. In qualifying, the best placed was the Charger, and even with its powerful Wedge 426 engine, it only managed 47th place with a time of 4:29.700 (56.1 seconds slower than the Alpine A442 that started on pole. During the race, both cars retired, as they had not been created to face the difficulties of such a long race.

5. Porsche 917K/81 Kremer (1981)

All motorsports fans know that the Porsche 917 was one of the most incredible racing cars ever created. What few people know is that, 10 years after winning Le Mans for the last time, a 917 returned to the French circuit to compete in the 24 hours. This is because Kremer Racing, a team specializing in racing modified Porsches, saw a loophole in the 1981 regulations that would allow a closed car to participate within the Group 6 regulations (this year was the transition year between the old Group 6 regulations and the newly created Group C). Taking advantage of this loophole, brothers Erwin and Manfred Kremer combined several components from the Porsche 917 with the aim of preparing a model capable of winning the race. Completed in record time, the project had the support of Porsche, which provided the original drawings, and the construction of a new car with aerodynamic updates, chassis reinforcements to withstand the new aerodynamic loads and updated suspension geometry to adapt to the performance of the new rubber compounds. When the race arrived, the lack of speed of what had once been the fastest car at Le Mans was clear, with a top speed of around 300 km/h on the Mulsanne Straight, resulting in the car qualifying in 18th place. During the race, the performance was not much better, with a retirement in the seventh hour of the race. It would have been the swan song for the 917, but Kremer decided to enter it for the 1000km of Brands Hatch, the last stage of the 1981 World Endurance Championship. There, due to a combination of the personal talent of the drivers (Bob Wolleck and Henri Pescarolo) and torrential rain, the 917 led the race until it retired on lap 43 with suspension problems.

6. Eagle 700 GTP (1990)

At a time when turbocharged engines were practically the norm at Le Mans (with the exception of Jaguar V12s), Eagle Performance decided to go for the best American style: they bought a Corvette GTP that had raced in the 1988 and 1989 IMSA seasons and installed a 10.2-liter V8 engine, the largest ever entered for a 24 Hours of Le Mans. Due to the need to install the new engine and adapt the car to the unique characteristics of the French track, the redesigned model became known as the Eagle 700 GTP. However, the car suffered electrical problems on the day of the qualifying test for private teams, which prevented it from qualifying for the race, never to be seen in competition again.

7. Toyota Supra GT 500 (1995-1996)

In the mid-1990s, after the dismantling of Group C, the organizers of the 24 Hours of Le Mans decided it would be a good idea to bring GT cars back to the track, modified sports cars that were the soul of the French race at the beginning. Taking advantage of the momentum, Japanese car manufacturers decided to enter their street models in the new GT1 category. Toyota, taking advantage of the development of the Supra for the Japanese Touring Car Championship (JGTC), thought it would be possible to win the category with its model, but what the manufacturer did not count on was that models such as the McLaren F1 GTR and Ferrari F40 GTE would also participate. Compared to models from Nissan (Skyline GT-R) and Honda (NSX), the Toyota proved to be competitive, but was about 15 seconds slower than the European models. Despite this, in 1995 the Japanese model was able to qualify in the middle of the grid (30th position), and finish the race in 14th position. For 1996 the Supra was revised, but the competition progressed much more, and even with the improvements it could only qualify in 36th place, failing to finish the race after being involved in an accident. In 1997 Toyota took a year off to come back with a car created specifically for the Le Mans challenge, the Toyota TS020 GT-One.

8. Panoz Esperante GTR-1 Q9 “Sparky” (1998)

If today hybrid powertrains and energy regeneration systems are standard in Le Mans Hypercars, the first car to compete with this type of solution appeared almost twenty years ago. Derived from the Panoz Esperante GTR-1 that competed in 1997 and 1998, the idea was to add a 150 hp electric motor to the vehicle, to recover energy during braking and then use it to help the combustion engine reaccelerate the vehicle, saving fuel which in turn would reduce the need for pit stops. Unfortunately, the model developed in partnership with the British company Zytek suffered seriously from being overweight, weighing 1100 kg compared to the 890 kg of the conventional model, as at the time battery technology was not yet at a point where they could be placed in a sufficiently light package, which led to the decision not to take it to the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Months later, the car would compete in the first edition of Petit Le Mans, achieving a respectable 12th place, but the model never competed again after that.

9. DeltaWing (2012)

Born as a proposal for a new Indycar model, the DeltaWing is the result of Ben Bowlby’s unorthodox thinking. To create the DeltaWing, he disregarded all the concepts then applied to racing cars, starting with a delta concept, without spoilers where all the downforce is generated by the diffusers under the car, creating a competitor with half the weight (475 kg), half the power (290 hp) and half the fuel consumption, with the same performance as a conventional car. Although the IndyCar organizers had chosen a more orthodox proposal from the Italian Dallara, Bowlby teamed up with Don Panoz (partner in project management), Duncan Dayton (Highcroft Racing team), Dan Gurney (builder of the car through All American Racers) and Nissan (engine supplier) to enter the project in the newly created Garage 56, a space for innovative cars to compete in the 24 Hours of Le Mans as invitees and prove to the world the viability of new technologies. Until the day of the first practice, critics believed that the car would be incapable of cornering due to its unconventional construction, with narrow front tracks and 72.5% of the weight supported on the rear axles, but during qualifying the DeltaWing achieved 29th position on the starting grid, right in the middle of the LMP2 class cars and showed excellent driveability and speed, but during the race it was hit by Kazuki Nakajima’s Toyota TS030 and was unable to return to the race. After that, the model competed in the American Le Mans Series and has been competing in the United SportsCar Championship in the P1 category, with reasonable results but with several reliability problems.

10. Nissan GT-R LM Nismo (2015)

If the DeltaWing had been a proposal that tore up the rulebook and was registered as an experimental vehicle, for 2015 Bowlby came up with an idea that followed the rulebook to the letter. Considering it was impossible to beat Audi, Toyota and Porsche by making a car like theirs (at least not if you spent a fortune on development), the idea with the GT-R LM Nismo (read more here) was to take advantage of the fact that the regulations allow greater freedom in the construction of the front wings than in the rear ones, in order to reduce the aerodynamic drag generated and reach higher speeds on the straights (one of the main factors for a fast lap at Le Mans, given the long straights of the French circuit). However, this would mean moving the center of aerodynamic pressure to the front of the car, and to maintain balance it would also be necessary to move the center of mass forward. The way to do this was to adopt a front-engine configuration, and to everyone’s surprise, not only the engine but also the drive was front. By doing this, the designer intended to have a car that was more controllable at high speeds and to face the unpredictable conditions of Le Mans, even at the cost of a car that was more prone to understeer. The engine, a 500 horsepower Cosworth V6 3.0 unit, drove the front, while a hybrid system based on inertial flywheels was planned to generate an additional 750 hp and send power to the rear wheels. The car was supposed to compete in the 2015 WEC season, however, development problems (mainly in the hybrid system) meant that the Nissan would only debut at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Even without the energy regeneration systems (which made them practically an LMP2 car), during training the models from the Japanese manufacturer reached the highest speeds on the straights and qualified in the last positions in the LMP1 category, and slightly ahead of the LMP2s, showing that the concept was valid, even if difficult to execute. During the race, all three cars entered suffered from reliability issues, and only number 22 finished, but without completing the minimum number of laps required to be officially classified. During 2015, Ben Bowlby’s team tried to solve the problems with the model’s hybrid system, but in December Nissan canceled the project and the car was never able to show its full potential.

BONUS: Peugeot 905 Spider (1992)

In the early 1990s, with the imminent end of Group C and the collapse of the World Prototype Championship (WSC), the organizers of the 1992 24 Hours of Le Mans faced a problem: the lack of enough cars to fill the grid. As a temporary solution, the ACO decided to make room for lightweight prototypes from national championships, creating the so-called Category 4 — a sort of improvised “Group B” to keep the tradition of the race alive. It was in this context that one of the most unusual entries in the history of Le Mans emerged: the Peugeot 905 Spider. Despite the name, these cars had little in common with the 905 V10 that dominated the endurance elite. Derived from a single-make category created by Peugeot to promote its sporty image, the small Spiders used 1.9-liter four-cylinder engines, based on the 405 MI16 block, delivering around 220 hp at 7500 rpm.

Lightweight, weighing just 489 kg, and built with an aluminum monocoque and carbon fiber body, the Spiders were designed for short races and not for an extreme 24-hour test. Even so, two examples were entered in Le Mans 1992: one prepared by the traditional French team Welter Racing, led by Gérard Welter, and another by the unknown Orion.

The difference in performance between the two teams was evident in qualifying. Welter Racing, with experienced drivers such as Patrick Gonin and Pierre Petit, easily outperformed Orion, which had rookies in the race. Despite their modest times, both managed to avoid the last row of the grid — and even outperformed a third car in the same category, the Debora SP92 with an Alfa Romeo engine.

In the race, as expected, the Spiders became mobile obstacles for the larger prototypes, being almost 200 km/h slower on the straights. The Debora broke down early, while the Welter car retired on lap 52 with suspension problems. The Orion was left to complete the marathon at leisurely pace: it crossed the finish line after 78 laps, but did not complete enough distance to be officially classified.

Despite the symbolic performance, Peugeot and ACO’s bold attempt paved the way for the future of the category. The failure of Category 4 helped shape the concept that would later give rise to modern LMP prototypes. An era ended in improvisation — and another was born, driven by ideas that emerged, ironically, in one of the most chaotic moments in the history of endurance racing.