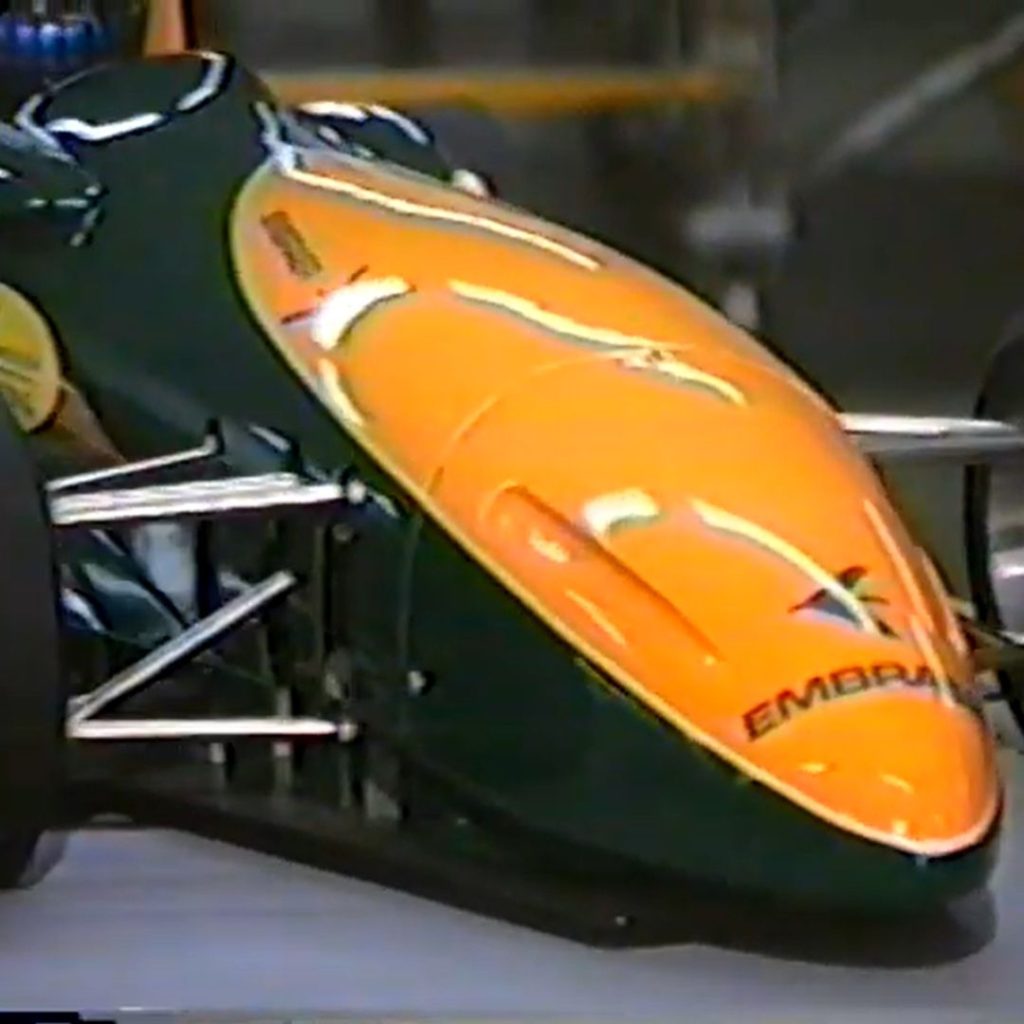

In the early 1990s, while Brazilian motorsports were undergoing a period of reinvention, a project emerged in São Paulo that had everything it needed to change the game. CLR — Chico Lameirão Racing — was officially founded in 1994 by two big names: engineer Lauro Carneiro Neto and legendary driver Francisco “Chico” Lameirão, Brazilian Formula Ford (1971) and Super Vê (1975) champion. But the story begins earlier, when the dream of building a Brazilian Formula 3 car took shape with the support of Embraer and the knowledge of a multidisciplinary team of specialists.

In the first half of the 1990s, Brazil was experiencing a period of industrial and economic transition. It was in this context that the CLR F3 emerged, a bold project to build a 100% Brazilian Formula 3 chassis, with direct application of aeronautical technologies — the result of an unprecedented collaboration between motorsport engineers and Embraer.

More than just a car, the CLR F3 represented a serious attempt to create a competitive product on the international market, incorporating conceptual innovation and technical excellence. Its proposal was disruptive: positioning the engine at the front, a structure made of composite materials, and an aerodynamic architecture that was believed to be superior to the dominant standard in the category at the time.

1. Project Conception and Philosophy

The project was born from the collaboration between engineer Lauro Carneiro Neto and driver and constructor Francisco “Chico” Lameirão, Brazilian champion in Formula Ford (1971) and Formula Super Vê (1975). Together, they officially founded CLR – Chico Lameirão Racing Technological Development in 1994.

The proposal was clear: to build a Formula 3 chassis according to FIA regulations, using high-tech materials and processes available in the Brazilian aeronautical sector. To this end, they entered into a partnership with Embraer, which at the time was still a state-owned company.

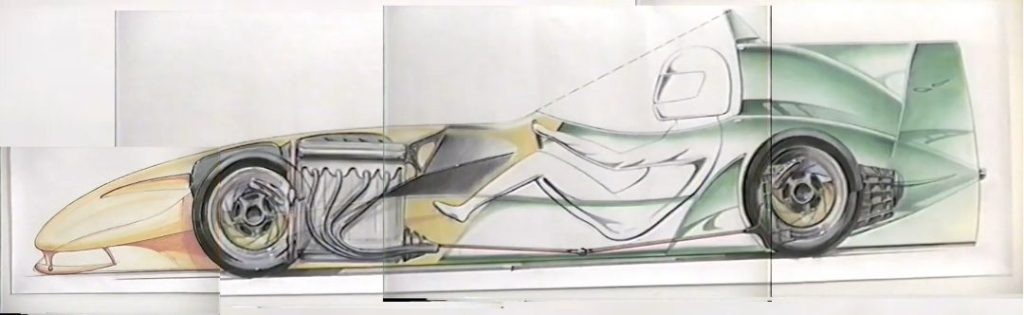

The technical concept of the CLR F3 was based on a front-mid engine, positioned in front of the cockpit, but set back in relation to the front axle, with transmission going to the rear axle via a cardan shaft. This architecture broke with the tradition of rear-engined F3s, seeking better weight distribution (50/50) and freeing up space for aerodynamic flow in the rear section of the car – a philosophy that decades later would be applied in a more extreme form to the Nissan GT-R LM Nismo.

With this layout, the aerodynamics were developed with technical support from CTA (Aerospace Technical Center), aiming to reduce drag, increase the efficiency of the diffusers and explore optimized bodywork configurations.

Furthermore, the project included a short wheelbase and suspension geometry optimized for slow and technical tracks, a trend that was growing in motorsport in the 1990s.

The technical team that led the development was composed of:

- Francisco “Chico” Lameirão – creator and responsible for the concept, body design and technical validation on the track. His practical experience in cars such as the Polar Super Vê directly influenced the configuration of the side boxes and the aerodynamic concept.

- Lauro Carneiro Neto – engineer responsible for the technical coordination and integration of the areas of structural engineering, vehicle dynamics and aerodynamics.

Wellington Ortiz Jr. – structural engineer, responsible for the structural analysis of the chassis, definition of load points, torsional rigidity and impact resistance. - Ricardo Bock – professor at FEI (Faculty of Industrial Engineering), he worked as chief chassis engineer, developing the monocoque and impact absorption systems.

- Ricardo Achcar – former pilot and businessman, he contributed with suspension geometry, dynamic evaluation and also worked in the commercial and strategic area.

- Marcos Lameirão – Chico’s son, provided technical and logistical support to the team during development.

The great engineer Ozires Silva, co-founder of Embraer and president of the company at the time, was also a great supporter. The integrated vision of this team aimed to align performance, safety and industrialization, with each specialist responsible for a key area of the project.

2. Embraer’s participation

Embraer, a partner in the project from the beginning, would play a key role in the technical feasibility of the proposal by providing its technical infrastructure, including CAD/CAE tools, telemetry tools, data analysis and processing, and the CTA wind tunnel. Embraer would also be responsible for a large part of the production process, including the carbon fiber monocoque, fairings, airfoils, suspension components, and final assembly, while CLR would be responsible for track operations and support, in addition to the technical know-how derived from decades of experience in motorsports and single-seaters.

3. Aerodynamic Concept and CTA Wind Tunnel Tests

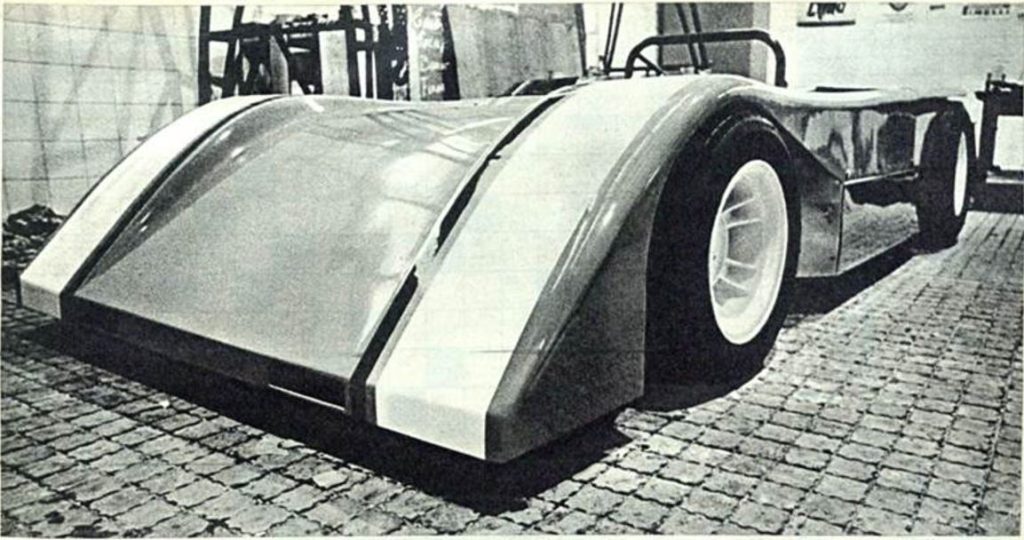

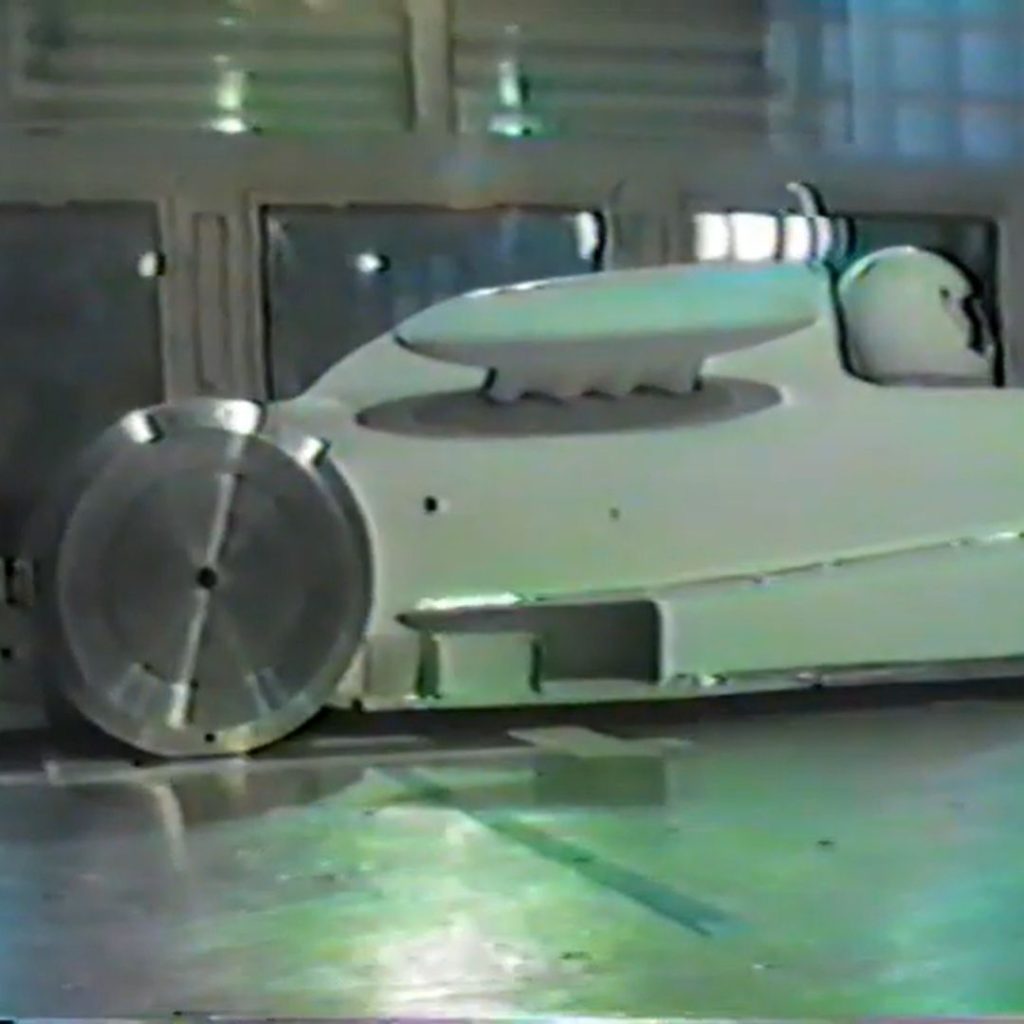

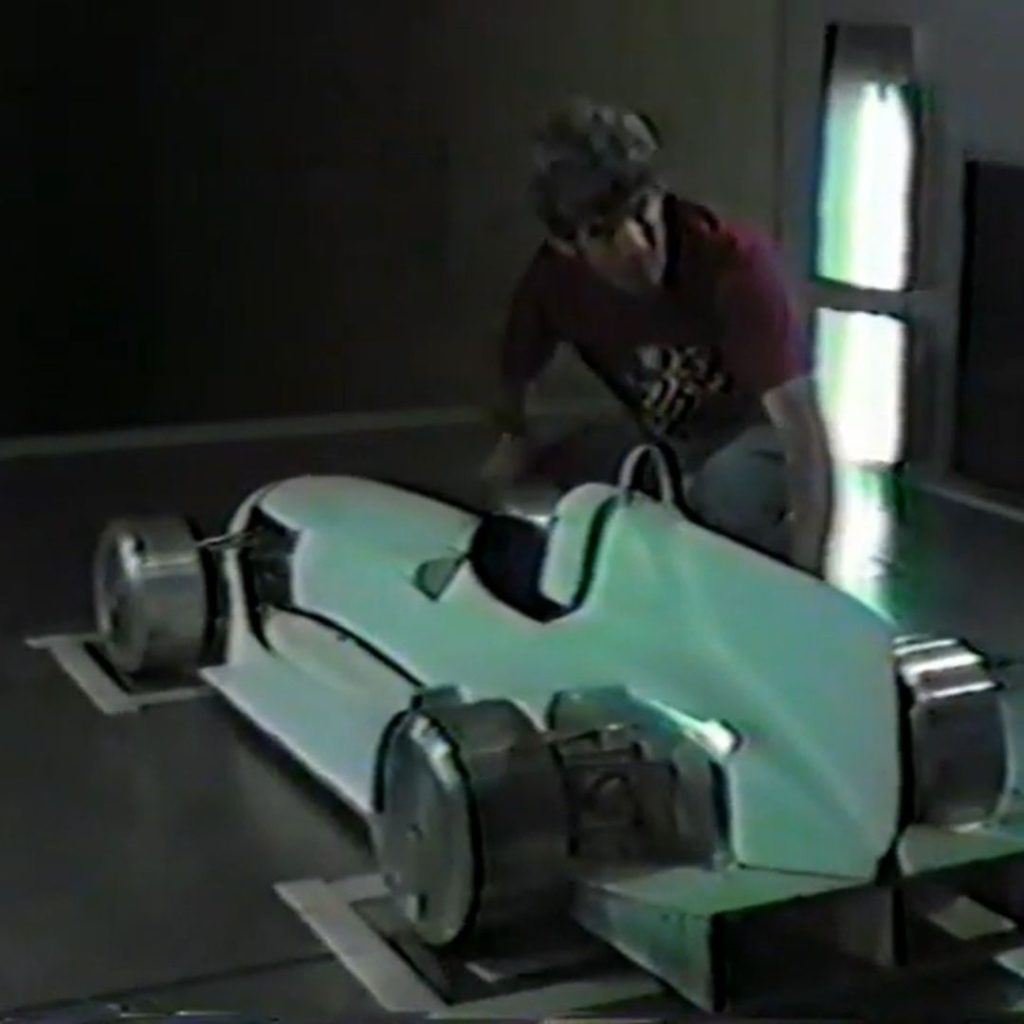

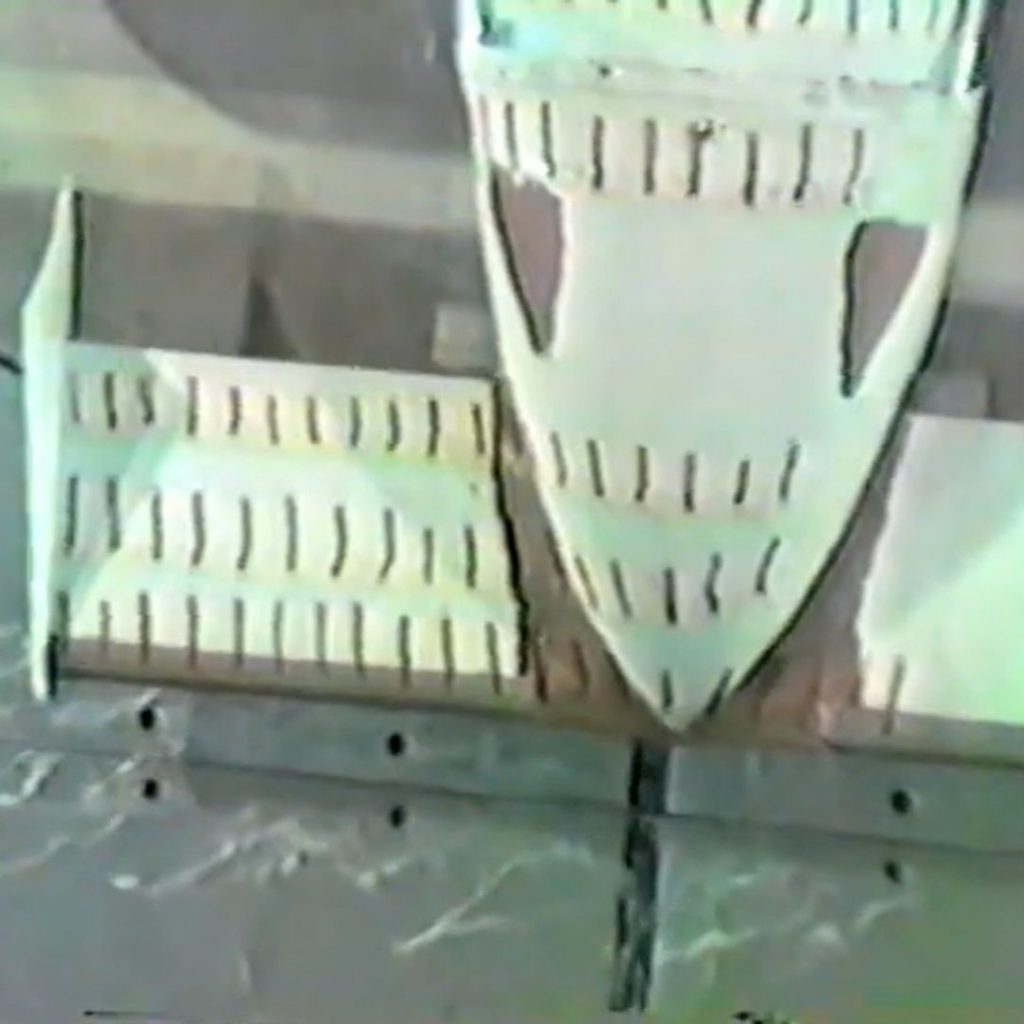

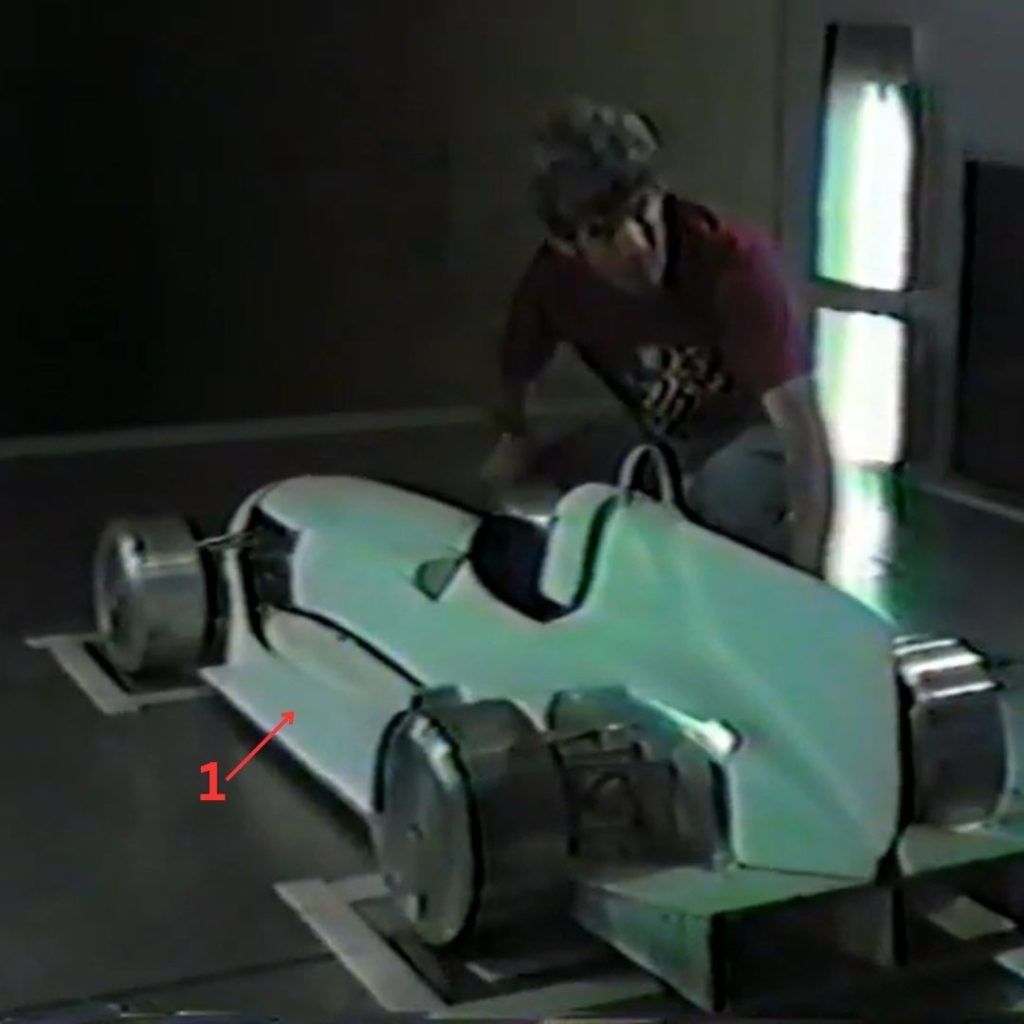

In 1993, even before the formal constitution of CLR, two 1:2.5 scale models were built: one of the CLR F3 and the other of a Ralt RT-35 chassis, then a reference in international Formula 3.

The concept developed by CLR resulted in a nose somewhat reminiscent of Formula Vee single-seaters, but with two air intake ducts.

In the final image of the painted model, the car appears without a front spoiler, but in one of the images it is possible to see that a more traditional configuration was also tested.

In the central section, the partial fairing between the front and rear wheels stands out, somewhat reminiscent of some F1 cars from the 1950s.

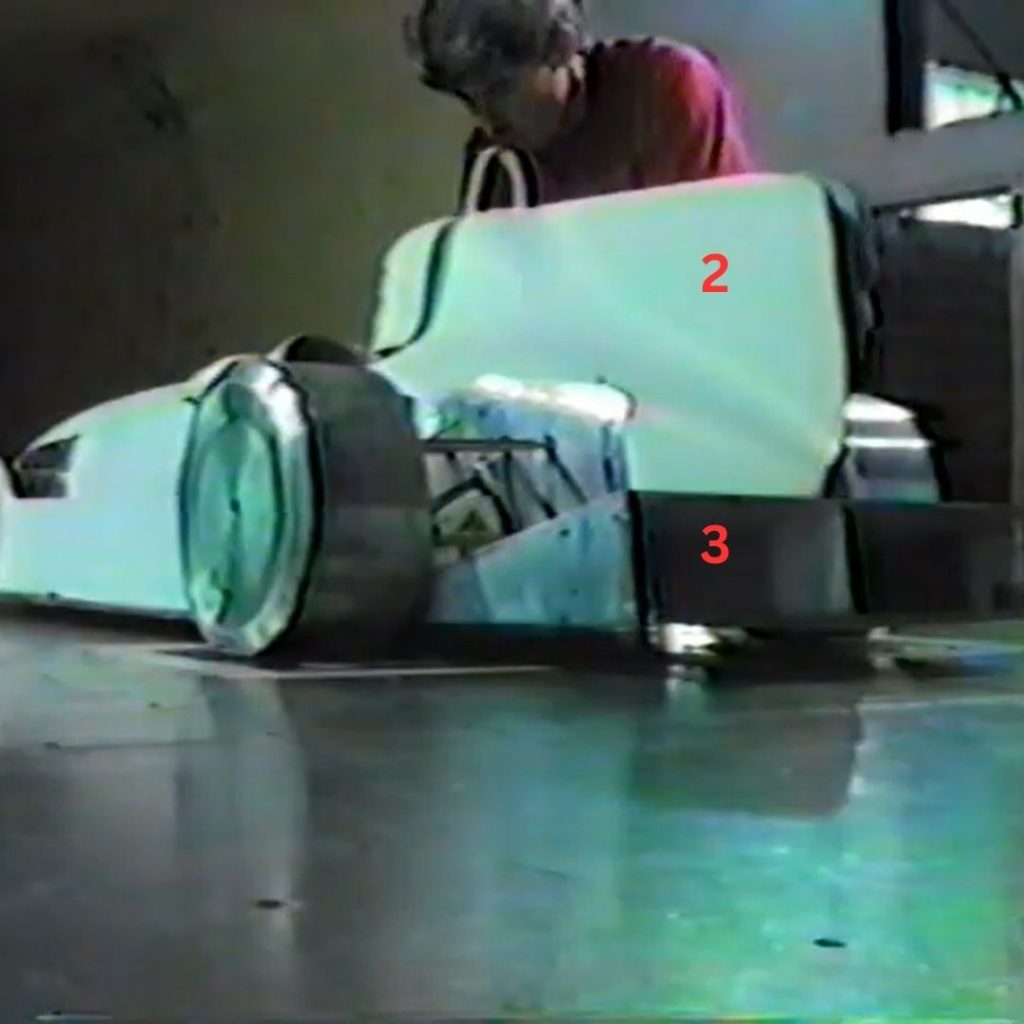

But the rear section is where the CLR F3’s biggest highlight lies, featuring a dorsal fin for greater stability (2) as well as a large diffuser (3).

In the painted model, it is also possible to notice the presence of two keels in addition to the dorsal fin – similar in concept to what would appear decades later in the first iteration of the Peugeot 9X8.

Aerodynamic tests in the CTA wind tunnel in São José dos Campos indicated the superiority of the Brazilian design. The geometry of the CLR, with a smoothly closed rear body, faired areas on the wheels and a reduced front section, showed in tests that the CLR required 20% less power to reach the same top speed as a Ralt RT-35 and was up to 28 km/h faster at similar speeds.

This data validated the adopted concept and paved the way for the construction of full-scale prototypes.

4. Manufacturing and Commercial Strategy

In the original plan, series production of the main components of the CLR F3 would be carried out at Embraer facilities, including:

- Carbon fiber monocoques

- Suspensions in aircraft grade aluminum

- Body structural components

CLR would be responsible for final assembly, delivery and support to the teams. The estimate – somewhat bold – was to reach a potential market of 300 units per year, competing in South American and European championships. Three cars were to be built initially, to compete in the South American, British and European Formula 3 championships.

5. Interruption and End of Project

The project was abruptly interrupted in 1994, due to the privatization of Embraer, which began to focus exclusively on the commercial and military aeronautical sector, ending external collaborations.s.

Without Embraer’s technical, financial and logistical support, CLR was unable to complete the prototypes or validate the model on the track. The dynamic testing and international homologation phase was never completed, bringing an early end to an initiative that combined innovation, cutting-edge engineering and industrial ambition.

6. Final thoughts

The CLR F3 Embraer was a visionary project that epitomized what Brazil can produce when technical talent, track experience and industrial structure come together. Its premature demise does not diminish the merit of its creators — on the contrary, it reinforces the value of national boldness and engineering in a field where it is rarely played at home.

At a time when automotive technology is once again seeking lightness, efficiency and systems integration, the CLR F3 remains a historical and technical reference, a reminder that innovation respects no borders — neither geographical nor cultural.

References:

CLR. Available at: https://www.lexicarbrasil.com.br/clr/.

CLR Embraer. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_q3taItU2c.